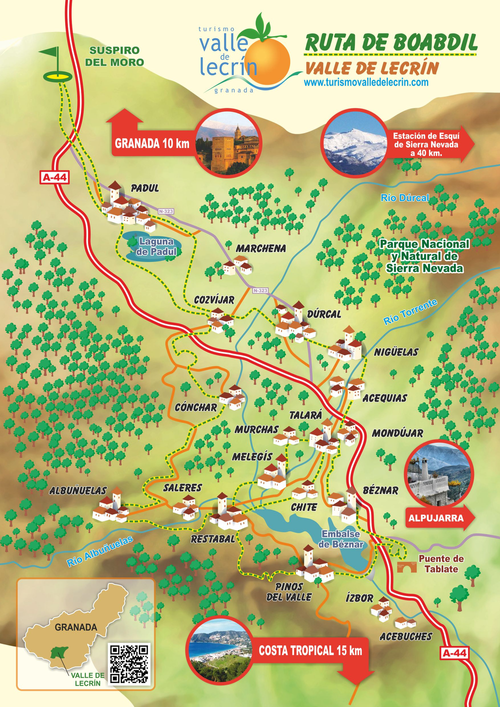

At the end of this story you will find some photographs of a few places in the Valley of Lecrín. I have also borrowed a graphic representation of the Valley of Lecrín created for Turismo Valle de Lecrin, an association of local business people about whom I know nothing except that their website is promoted by the provincial government of Granada. I guess they are boosters. Anyway, the photographs and the colorful map will help you visualize the places I am about to describe.

The following story is true.

You will find the Valley of Lecrín in the province of Granada on the western edge of the Sierra Nevada in Spain. I first travelled there in 1979 when I was a student at the Universidad de Granada in the Cal State University Study Abroad Program. Students from all over the world congregated five mornings a week in a handful of classrooms in a small palace on the corner of the streets Puentezuelas and Obispo Hurtado. The little palace is still there today, but the Program has moved somewhere else. In one of those classrooms, we studied Geography with a Professor we fondly referred to as “Dr. Epaña Húmeda.”

There were exactly eleven of us from California. We were the only Americans in the Program. The other thirty or so students mostly came from western Europe but also from Japan, Canada, and a few other places I can’t remember. So, I guess I exaggerated when I said from all over the world. But, as I was from a small town in California, at the time it seemed to me like they came from everywhere.

Dr. Húmeda conducted his Geography class every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings at ten. He was a native of Granada. Consequently, he routinely dispensed with certain intervocalic consonants, a custom of speech peculiar to Andalusians but especially pronounced in my new home. For example, locals did not call their city Granada. They called it Graná. Why bother to say the d? Just breath a little more life into the second a and you’re good to go.

The same was true for the name of the entire country. Don’t say España. Say Épaña. Who needs that s anyway? Granadinos certainly live without it very comfortably. And so did the Professor. Those of us trained in the more traditional Castellano spoken in Madrid, well, we got used to the Professor pretty quickly I have to say. He talked funny but he was charming and well informed. He entertained as he lectured.

Why did we add the Húmeda to his nickname? Because one of his first lessons was to let us know that Spain is divided into two basic regions: España Húmeda and España Seca. Most of Spain, including Granada (and consequently the Valley of Lecrín) lies in España Seca. Only the northern part of Spain can claim to be wet: from the north slope of the Cantabrian Mountains to the Bay of Biscay. It’s a lesson I obviously have not forgotten in over forty years. That part of Spain has a climate more like Southern England than what you imagine Spain to be like—warm and sunny all the time. Up there you can find the Camino de Santiago, a 500 mile pilgrimage thousands attempt every year as an act of faith or as just an excuse for a long but glorious hike.

Meanwhile down here in southern Spain, the weather is usually sunny and warm, and it was a nice fall Saturday when the Professor loaded up his class into a large bus for a day-long field trip to the Costa del Sol. The itinerary was to leave Granada over the Suspiro del Moro, drive into the Valley of Lecrín for a brief stop to discuss the Minifundios prevalent in that part of Andalusia, continue on upriver through the Valley of the Rio Guadalfeo, climb into the Sierra de la Contraviesa, stop at a winery in Albondon, and finish up at the Playa el Ruso before heading back to Granada.

It was quite a day I can tell you. When we got to the winery, they not only gave us a very nice tour, the vintners also served out one glass of wine after another. As much as we wanted. And we wanted quite a lot. It was by far the best wine tasting experience of my entire life. It was nearly enough wine to suffice for all the other wine tasting I have done since. To top it off, as we boarded the bus for the beach, the winery gave each and every one of the students a full unopened bottle of wine to take home. Very few of those bottles got home unopened that day. The bus driver and the Professor were exceedingly tolerant men.

Long before we ever got to the winery, as I was saying, we had to drive through the Valley of Lecrín. This valley, some of which looks like a valley and some of which was more of a canyon back then, starts the moment your vehicle crests the Suspiro del Moro on its way south to the coast. The Suspiro del Moro is a mountain pass about 860m meters above sea level. History records that the last Moorish King of Granada, Abu Abdallah Muhammed XII, also affectionately known as Boabdil, turned his horse around at this pass and wept as he took a long, last look at the city from which Ferdinand and Isabel had just expelled him in 1492. A lot happened in that year.

Back then, not 1492 but rather the fall of 1979, the journey no longer needed to be made on horseback or on foot. You could drive a car or a bus. It nevertheless took quite a lot longer than we are used to today. You see, there was only one two lane highway to the coast, and it passed through most of the towns and villages on its way. Today there is a four and six lane freeway that permits the traveller eager to arrive at the Mediterranean Sea the luxury of skipping the narrow and convoluted streets and the slow moving pedestrians of Padul, Marchena, Durcal, Mondujar, Talará, and Béznar before zooming out of the valley over the fantastic European Union sponsored bridges spanning the reservoir at Rules on the Rio Guadalfeo. On a good day now it takes forty minutes to go from Granada to Salobreña on the coast, and that’s if you keep the speed limit. If you drive the way some Spaniards do, you get there in less than a half hour. In 1979, however, even by car, it was a journey of at least two hours.

As we eager students entered the Valley of Lecrín from the north on the old highway, we could spot Padul and its natural lagoon. Then the bus rumbled down into the town. Padul was the largest town in the valley, and it is still the largest today. Marchena, then as now, had just a hundred or so residents. Then came Durcal, Padul’s rival. It’s main street narrowed to only one lane as the bus approached the city’s square. It is still just as pinched today but now is a one-way street. Back then you took your chances coming or going.

The expanse of land from Padul through Durcal has a semblance of a valley. There are broad low sloping hills framed by the indominable Sierra Nevada Mountains on the left and much lower but nevertheless rugged highlands on the right. On the approach to Durcal, however, we got a preview of what was to come when we crossed the Rio Durcal spilling down from the Sierra. Through a series of switchbacks we descended from the high plain of the valley into the river gorge and down to the old stone bridge that provided safe passage across the river to access the town. To maneuver on these hairpin turns, the bus consumed the entire highway. In fact, the entire day’s itinerary traversed rugged terrain. Over the course of that day’s journey, the driver must have had to execute this operation hundreds of times. We passengers only took notice when the turns accompanied a route along the face of a cliff. But that happened often enough to be memorable as well.

From the southern end of Durcal today you can still find the old highway and drive it all the way down to Velez de Benaudalla, which is south of the reservoir at Rules. So this experience is open to anyone who would like to recapture some of my personal adventure from back then. The old highway is tortuous but kind of fun. Between Durcal and Mondujar, the highway crosses the Rio Torrente on an old stone bridge. My friend Gonzalo has an olive orchard along that river just downstream from the bridge. You can see the ancient grey-green trees from the highway. But keep your eyes on the road if you’re driving. I am pretty sure the highway has been improved over the last forty three years but there are still blind curves and no passing lanes. You have to take it slow.

Our bus did not stop, except for pedestrians or donkeys, until we arrived at Béznar, the village where I reside today. I did not know it then, but Carmen grew up there. A few years later, I married Carmen.

At that time, Béznar had a church, a bar, and a grocery store. It boasted a population of over 600. Today it still has a church and a bar, but the grocery store closed about ten years ago. The population has diminished to about 300.

Also back then, the big dam on the Rio Izbor did not exist. From Durcal through Talará and all the way down to the Rio Guadalfeo, the Valley of Lecrín was really more of a canyon than a valley. The villages that had sprung up over a few thousand years sat precariously on ledges here and there along the mountain side. Humans were obviously attracted to these ledges of one hundred acres or so because the terrain on top of them was manageable for agriculture and because it was there humans found an abundance of water. These ledges sit near the bottom of a mountain range that has peaks over 12,000 feet high. Those peaks are only several miles away from the valley’s villages as the crow flies. Year after year after year, the mountain peaks supply water. Natural springs abound and can still be found here and there on treks through the lemon and orange groves around Béznar. But most of the water has been organized into districts and directed into canals so that the village farmers can routinely irrigate their orchards. Like the villagers and their ancestors, these orchards find a home clinging to the mountainside ledges.

And that brings me back to my Geography Professor, Dr. Húmeda, and the reason he had the bus stop in Béznar. In the classroom, he had explained to us that the problem with agriculture in the province of Granada was that the land was broken up into parcels that were too small to support a viable and prosperous economy. Béznar was a prime example of this misallocation of resources. The land had been held for generations in parcels no bigger than ten acres. Some of the parcels did not amount to even a half-acre. The ownership likewise was distributed through inheritance to such a degree that some plots of land were no bigger than a lot for a house and a garden. Nobody could really make a living from agriculture on parcels that small.

However, the thing I noticed then and still notice today is that the place seemed like a little paradise. The village was quiet and peaceful. The orchards were well tended and orderly. Yet they seemed to fit in naturally with the landscape. The orchards were part of the contours of the land. They did not disrupt the terrain. They complemented it.

Indeed, to look at the terrain, one has to wonder how anyone had the temerity to engage in agriculture there at all. Humans had carved out gardens from the side of a granite mountain. And back then, those gardens continued up the mountainside thousands of feet in elevation and graced the canyon walls all the way down to the banks of the Rio Izbor. A couple of years later, my future brother-in-law, David, gave me a guided tour of the orchards of apricots and peaches that clung to the terraced canyon as we trekked down to the river and up the other side to the town of Pinos del Valle. The little canals full of rushing water seemed to follow our every step and sung delightful melodies to compete with the songbirds that flitted from stonewall to tree branches. It was marvellous.

That trek is no more. In the 1980s the government appropriated the land, built a dam on the Rio Izbor, and flooded the canyon. But the land that has not been flooded is still farmed today by the people of Béznar. Those who farm the large lots of five or ten acres still live in town. Most of those men are in their seventies now but there are a few younger men around too. The younger ones all have day jobs because the Professor was right: you cannot scratch out a living on a few acres of canyon land.

Reading about your day trip four decades ago and about the changing landscape due to the modernization of infrastructure was well worth the break from work! It was such an enjoyable read that I want to travel to the valley to experience it for myself! Farming is a challenge everywhere as children and grandchildren respond to the siren song of the city and a career that does not entail waking at 5 a.m., fighting pests, working the harvest, and pruning in the early spring.

Love your story. I can imagine being in the same room with you hearing it. Hope to see your corner of the world someday. Very different from where I am and work now.

El “valle alegre”, “vallis alacris” llamaron los romanos al Valle de Lecrín. Tu relato me ha alegrado la noche. También me ha puesto nostálgico.